September 18, 2023Blog“The class gave me hope and optimism… about how we can collectively seek justice for animals, which I translated into ideas for my design proposal.”

Rebecca Shen was one of several cross-registrants who took Professor Kristen Stilt's animal law class this past spring. The class helped inform her Master's thesis project design, which is to turn feedlots in California into cow sanctuaries. Here, she shares more about her motivations for her work and for taking the class.

By Rebecca Shen

In my final year of the Master in Landscape Architecture program at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, I completed a design thesis, advised by Francesca Benedetto. I had initial interests in animal rights and the environmental impacts of intensive cattle feedlots. This past spring semester, I was also fortunate enough to cross-register and take Professor Kristen Stilt’s class, Animal Law. Taking this class was transformative in knowledge-building for my thesis. I was exposed to the wide range of approaches to advocate for animals within the legal system but was disheartened to learn that advocating for farm animals, or “food animals,” proved to be the most challenging. Advances for farm animals seemed to come predominantly from a welfarist perspective, far from the idealistic post-meat future I envisioned for the setting of my thesis. Despite the oftentimes disappointing, heartbreaking, and bleak reflections of human-animal relations in the cases we studied, the class gave me hope and optimism through the passionate discussions about how we can collectively seek justice for animals. I do believe that momentum is building in animal advocacy.

Rebecca at her final thesis review captured by Austin Sun.

Landscape as a general field of study has facilitated the invisiblization, instrumentalization, and condemnation of animals. For example, cows, and other “livestock,” are rendered as passive agents and aesthetic props through the romanticization of the pastoral landscape, as well as through the geospatial separation between humans and sites of animal production. Throughout American history, cows have been instrumentalized in the projects of colonization, land grabs, and post-war industrialization. In California especially, the cattle frontiers became “the driving force behind Euro-American political and commercial domination, under which native residents lost land and sovereignty…” (John Ryan Fischer, Cattle Colonialism). The overbearing land use of the animal agricultural industry and the fraught history in which domesticated animals have been entangled in capitalistic conquests of land and people need to be critically confronted.

As a design student, I believe it is pertinent to build bridges between disciplines. For me, this means taking the theoretical underpinnings of animal rights explored so extensively in animal law and imagining how landscape architects may take them seriously in our venture to design more just landscapes for humans and nonhumans alike. As Kevan Klosterkill wrote, “When the particular biases that inflect human-animal relations are taken seriously, we gain another window into how landscapes function as broader world-making projects.”

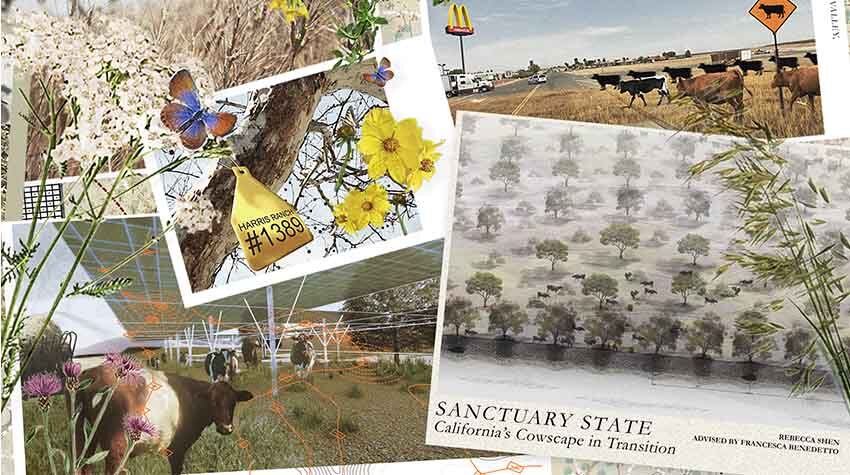

Design Thesis Abstract

My final design thesis is called Sanctuary State: California’s Cowscape in Transition, is a worldmaking scenario, set in an idealized future in which cows are not exploited for meat or dairy. The design transforms an 800-acre feedlot into a sanctuary, a healing site for cows. Feedlots, common in California’s San Joaquin Valley, are degraded landscapes that demonstrate fraught human-animal relations that invisiblize, instrumentalize, and ultimately condemn domesticated animals. While cows have been implicated in over 10,000 years of domestication, the feedlot-to-sanctuary transformation envisions alternative relationships with animals in a future where transitional interspecies justice is achieved through ecological reparation and animal liberation.

Humans must first dismantle the feedlot to initiate the restoration, in the process confronting the injustices of mass animal production. Infirmaries replace slaughter loading docks, woodlands memorialize cow passings, perennial plantings remediate the damaged soil, and waste accumulates into feral habitat islands that entice cows to meander and forage. Cows and other beings participate as co-designers, revealing the feral sociality of the site’s post-industrial reality. Feral ecologies and self-determining animals, at the sanctuary and the Valley beyond, establish themselves as agents of resistance and growth in the most degraded of places and situations.

The Site

Harris Ranch is the largest CAFO, or Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation, on the west coast of the United States. The feedlot is 800 acres and consists of a barren dirt floor holding between 70-100,000 cows at a time. Cows live at industrial feedlots until they reach their desired weights before slaughter. Unfortunately, this feedlot is rather mundane in the San Joaquin Valley, where the Harris Ranch feedlot is just one element of an expansive geophysical cowscape powered by fossil fuels, emitting greenhouse gases, and hosting millions of confined animals.

Harris Ranch is straddled against Interstate-5, an opportunity for public visibility as the landscape transforms. The project will take cues from the site’s pre-colonial and pre-feedlot vegetative characters, which was native grassland and scrubland set between chaparral, woodland, and riparian ecologies. Through the forced introduction of cows to a landscape it is not native to, the site has undergone deep disturbance from intensive land conversions of native grasslands to industrialized feeding operations.

The layout of the feedlot was designed for maximum efficiency, density, and productivity. The lot includes about 600 acres of holding pens and loading docks and 200 acres of large manure pits in which manure and lot runoff is stored.

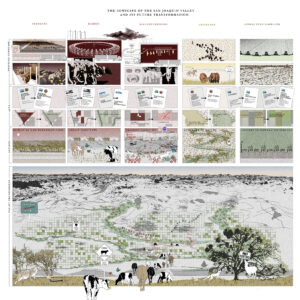

Confront, Dismantle + Repair, and Heal + Co-design

To set the stage for this thesis, social and climatic collisions force us to reckon with the animal-industrial complex. Such collisions and events include anarchy, divestment from animal agriculture, self-freeing cows, social justice movements, and climate reckoning. In my thesis, CAFO operations end in the near future from these pressures. The Harris Ranch feedlot site then commences a massive dismantling and ecological restoration, underpinned by goals of flourishing, codesign, and kinship.

The design proposal intervenes in four broad material ways. Each of the four material processes is framed through actions over time: confront the standard industry landscape practice, dismantle and repair, and heal and codesign.

First, we confront the manure mounds. Manure mounds are currently held in the cows’ feedlot pens and removed every few months for agronomic application. A thick crust of compacted manure has also formed over the mineral soil, a common phenomenon across feedlots that changes the very chemical composition and structural integrity of the soil. I propose for the mounds to remain on site and accumulate contaminated soil over time during the process of scraping off the compacted manure layer. They become stark post-industrial landforms upon which superpower, manure-loving plants may take root and begin to remediate the mounds’ substrates. After the planting and dispersal of seeds, feral growth takes over the mounds, and weeds and other plants continue to be spread by cows who forage them. This process was witnessed at my fieldwork at VINE Sanctuary, where mounds of waste transformed into feral habitats.

Secondly, we confront the existing sprinklers on site. The sprinklers, aligned with the fence grid, use immense amounts of water to keep the thick dust clouds, ammonia, and temperature down but create a muddy ground condition that often means cows are standing knee-deep in their own liquid feces. I propose for these sprinklers to initiate the logic for crop circles, watering heavy feeder cover crops whose roots help break down the compacted soil and take in its excess nutrients. Over time, the annual crop circles transition into perennial pastures, through which the cows forge new paths and new ecologies.

Next, we confront the open-air manure effluent pits, notorious across CAFOS for storing liquid manure and runoff and emitting high amounts of deadly gases. This feedlot in particular produces as much as 150,000 tons of manure annually. I propose the transformation of the pits into anaerobic gardens and terraced constructed wetlands that treat wastewater through the infrastructure of plants. Garden construction begins around the higher pit elevations to catch and retain feedlot runoff intermittently. Subsequently, terraces are constructed in the lower pit elevations. Over time, as the pits dry up and cow density diminishes, planted willows and wastewater filtration plants establish their roots. Across wet and dry seasons, the gardens host numerous animal communities, including cows who make gathering enclaves within the gardens of their choice.

Finally, we confront the act of processing pre-slaughter cow mortalities as industrial waste in compost windrows. Currently, the industry sees many mortalities from various industry-induced causes before even reaching the slaughterhouse. I propose a dignified burial for cows in sanctuary, by which their bodies are simply not converted to the commodity they were bred into existence for. Instead, cows rightfully return to the earth in whole. Each passing of life is marked by the planting of a new tree or shrub. Over time, this sanctuary memorial expands and grows as cows pass, and the cows’ bodies bring new life and abundance to the site. Attached to each tree marking a buried cow is an ear tag, a representation of cows’ transition from property to self-actualized being.

Transformation

The dismantling process of the site is phased over about five years. The pen fences are torn down one area at a time, and cow infirmaries replace the previous loading docks. During this time, cows rotationally graze in the foothills of the Diablo Range, crossing a corridor over the interstate. The woodland cemetery is initiated as a couple thousand of the feedlot cows pass. Cover crops, pasture grass, woodland plantings, and wetland plantings begin to repair the site ecologically. Cows heal by foraging rotationally amongst new plant palettes, a relief from their feedlot diet of grain and corn.

In 5-15 years, planting communities evolve, the pits dry up, and the human-initiated choreography of the site begins to take on a more unruly character. Cows begin to explore wider terrain; their paths across the landscape become more legible. Perennial pastures replace annual cover crops, and the woodland expands with each cow passing, creating a buffer between sanctuary and the interstate. As the woodland grows over time, the formal geometries of the plantings merge, creating masses of tree canopy. The mounds grow into organic landforms that are quickly colonized by feral plant growth, becoming new foraging grounds. The mounds’ physical and chemical forms also evolve by plants, erosion, water, gravity, and cow hooves.

By 15-20 years, most of the original feedlot cows have passed, reaching their natural lifespans. The landscape now finally has a semblance of balance between cows and acreage, and the site is revegetated as much as possible within the 800 acres. But the cow community is not gone entirely. The remaining residents are rescued off-site cows or descendants of passed feedlot cows.

I extrapolated the cows’ circulation by imagining how certain individuals I observed during my ethnographic fieldwork at VINE Sanctuary (a forested farmed animal sanctuary in Vermont) might inhabit this landscape, inspired by their curious range and routines that are imprinted onto the landscape.

Acts to Transform the Valley Landscape

How might the San Joaquin Valley look like in a state of sanctuary? The valley’s existing cowscape currently consists of three broad categories: industrial CAFOs, fodder cropland, and rangeland. Alternative acts shall transform the Valley, giving sanctuary rights to animals and nature, for the benefit of the entire land community. The main act is the Animal Liberation Act, targeting places of mass industrial confinement: feedlots, dairy CAFOs, and slaughterhouses. It is a radical re-imagining (or denouncement) of the federal Animal Welfare Act. The Animal Liberation Act declares that animals have rights to be free from confinement and exploitation, which means they now also have rights to sanctuary. All CAFOs in the valley cease operation, as we’ve witnessed in the transformation of Harris Ranch, and the act initiates a network of sanctuaries, especially near human populations. Not all CAFOs transform into sanctuaries, as some are better suited for conversion into agricultural land.

The Cropland Conversion Act, extending from the realization of the Rights of Nature, returns some animal croplands—consisting of hay, pasture, and grain fields—back to nature, creating a contiguous nature sanctuary corridor surrounding the valley’s historical and vital river system. The remaining fodder lands are transformed into alternative croplands, producing food directly for humans, not cows.

Finally, the Bureau of Land Management’s private grazing permits and open rangelands are handed over to the animal and nature sanctuaries. Ranching no longer exists after the Animal Liberation Act, and all open rangeland becomes solely public lands that may be dedicated to the public nature and animal sanctuaries across the Valley.

The human-initiated acts begin reparations to animals, but over generations of dismantling, healing, and adaptation, domesticated and wild animals establish feral relationships as they already are in the Anthropocene, blurring the line between the domesticated and wild worlds.

This project ultimately envisions a more just world for animals if we take their flourishing, agency, and kinship seriously. Cows’ agency to inaugurate landscapes through their own perception, made visible through the creation of sanctuary, instills hope for a future of transitional interspecies justice and coexistence.

SANCTUARY STATE from Rebecca Shen on Vimeo.